This morning, I was thinking about the several different types of techniques of baguettes that I make: Pointage en Bac, Baguettes de Tradition, Poolish, Levain, Poolish, and Sourdough, Sourdough and Yeast; not to mention varying the hydration and flour blends to achieve different textures. The baguettes pictured above are Poolish and Levain baguettes ala Tartine Bread. They’re a low hydration double preferment bread that produces a crunchy crust and a chewy crumb. My Baguettes de Tradition on the other hand create a light, crispy crust with a light, airy crumb.

In any case, I realized that I use two dough development techniques depending on the type of rising agent I use: One for yeasted and another for sourdough. So I thought I’d share them here so I could just link to them in my future baguette recipes as I’m tired of duplication.

Flour Type

People ask me what flour I use for making baguettes. Traditionally, baguettes are made with white flour. But unless I’m teaching a basic technique or introducing a new recipe, I invariably use a mix of different kinds of flour to affect different flavor profiles in my bread.

Sift Your Flour!

Whether or not you use a blend of different flour, you should always sift it before mixing. This will prevent large lumps from forming during the mixing process.

Yeasted Baguette Dough Processing

Mix. Mix all the ingredients together to form a shaggy mass. With my yeasted dough baguettes, I normally don’t do an autolyse.

Bulk Fermentation. 1 1/2 to 2 hours or 6-18 hours in the fridge. Bulk fermentation is finished when the dough has expanded about 50%.

Folding. Whether doing a cold bulk fermentation or not, stretch and fold the dough every 20 minutes in the first hour. By the third fold, the dough should be smooth and luxurious and will be highly extensible.

Levain Baguettes

Whether I’m making a double-preferment (both poolish and levain) or just a straight levain dough, I use the same process for both, which leans heavily on Chad Robertson’s dough development technique.

Initial Mix. Reserve 50g of the water and set it aside. In a large bowl, dissolve the preferments(s) into the remaining water to create a slurry. Add the slurry to the flour and mix until no dry ingredients are left and you’ve formed a shaggy mass. Cover and allow to rest 30-60 minutes.

Final Mix/Bassinage. Sprinkle the salt over the dough, then add the reserved water to the bowl. Work the salt and water thoroughly into the dough until all the water is absorbed and you can no longer feel any grittiness from the salt.

Bulk Fermentation. 3-4 hours @ room temp. Bulk fermentation is complete when the dough has expanded about 25%-30% in volume.

Folding. Fold up to 6 times every 30 minutes for 3 hours. That said, really feel the dough and check its extensibility before each folding session. This folding schedule is based on the Tartine method which calls for 6 folds over 3 hours. However, I’ve rarely gone past 4 folding sessions with the flour blends I use – they get strong real fast, even if I’m handling them gently!

Once you’ve built up dough strength, you can either proceed to shaping or pop the dough into the fridge for further flavor development from 8-18 hours.

Both Yeasted and Levain Baguettes

Divide and Pre-Shape. All the baguette recipes I post here either make 4 X 335g baguettes or 6 X 220g baguettes. Whichever you choose, divide the dough into pieces of that weight. Once divided, letter fold each piece by stretching one side, then folding it to the center, then stretch the other side and fold it over the body of the piece. Then roll the piece up like a jelly roll perpendicular to the folds, seal the seam, then place the piece seam-side-up on a well-floured couche.

Shape. I use Master Chef Markus Farbinger’s shaping technique. There are others out there, but this is the one I know. Feel free to use one with which you’re familiar.

No matter the shaping technique you use, bear in mind that shaping a baguette is not just rolling the dough into a long, skinny log. The first part of getting it into a cylindrical shape builds skin tension prior to rolling it out. This is absolutely critical to achieve ears on your cuts when you score! I will submit that this particular step is the most important step of shaping.

Final Fermentation: Depending on the ambient temp of your kitchen, final fermentation can take anywhere from 30 minutes for yeasted baguettes to 2 hours for levain baguettes. In either case, to determine when the loaves are ready for the oven, poke a floured or wet finger about a half to three-quarters of an inch into a loaf, then pull your finger back quickly. Observe the rate at which the indentation comes back. If it doesn’t come back at all, pop the loaves into the oven immediately – you’re extremely close to over-fermenting the dough. If it comes back quickly, and almost fills the indentation back up, give it a bit more time. If it comes back quickly, but immediately slows down, then you’re ready to bake!

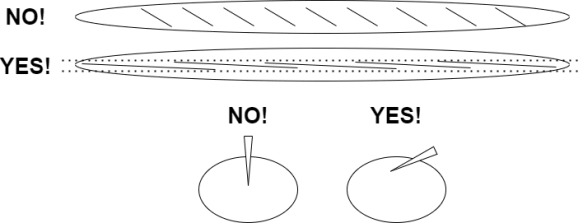

Scoring. Scoring should be done in the middle third of the loaf, using fairly straight lines that overlap each other by about a third. The lame or scoring blade should be at an extreme angle to create a flap which will in turn bake into an ear as seen in the picture below.

Don’t cut across the loaf! This will only create diagonal slashes!

Though Chef Markus mentions overlapping the scores, he doesn’t discuss why you need to do it. If you don’t overlap the scores, your baguettes will indeed open at the scoring sites, but they’ll come out as bulges and remain narrow where the cuts didn’t overlap, so the sides of your baguettes will be wavy, not straight.

Baking. Bake at 475ºF with steam for 12-15 minutes or until the loaves start taking on color. Vent the steam and remove your steaming container, then bake for 12-15 minutes at 425ºF or until the loaves turn a nice, deep, golden-brown.

Alternative Baking Method. Bake at 400ºF for 20 minutes with steam. Remove the steaming container, then finish baking at 425ºF for 25-30 minutes. I know it sounds backward, but it actually works great!