I woke up early this morning with a question in my head: Am I being a bit too academic with my bread-making? Like many bakers, I live by my formulas. They ensure that my loaves are consistent, no matter what I bake. But it occurred to me that bakers long before me had been baking by feel for centuries. They’ve developed a certain instinct about how their dough should look and feel.

Then I remembered watching four-part series on Netflix by Michael Pollan called Cooked. In the bread episode, there was a woman who made her bread in a wide bowl, just adding her ingredients in a seemingly free-form manner. It was fascinating watching her work! Then I harkened back to a video I saw of an Amish farmer making bread. No measurements, just going by the consistency of his dough. Again, fascinating. Then finally, at the world-famous Poillane Bakery in Paris, the bakers don’t use any measuring devices. They study the process for a year and a half!

That got me thinking: Have I developed those kinds of chops? After all, I’ve been baking bread for over 40 years. And especially in the last year, I feel I’ve developed certain instincts of how my dough should look, feel, and behave. So I decided to challenge myself today and go completely native, that is, use absolutely no measuring devices of any kind to assemble my dough.

The Starter

I had tailings leftover from my bake yesterday, so I fed my starter this morning with some AP flour, eyeballing the flour and water to relatively equivalent amounts.

I’m going to do something a bit different once it’s ready to be used and that is to mix it with a large quantity of water, then gradually add it to some flour until I get a consistency that’s similar to 65% to 70% hydration dough. This is consistent with what I do already by dissolving the starter in the water (sans a reserved amount for bassinage), then adding that to the flour.

I’ll let that mixture autolyse for a half-hour or so, then I’ll add the rest of the water and the salt, which I will also eyeball. Truth be told, I eyeballed what I think is 20 grams of salt based on the little crucible that I normally use for weighing my salt.

I am going to do a bit more of a bassinage. Normally, it’s about 50 ml of water. I think I may reserve more. I’ll play that by ear. Once I have the mix to the consistency I want, then I’ll do the standard 3-hour bulk fermentation with folds every 30 minutes or until I get about 25%-30% expansion.

I’m a little torn right now about the dividing and shaping. I’m a little anal about things being equal, so I’m leaning towards dividing my dough using a scale. But we’ll see when I get there… That said, I just might not do that to see if I have the chops to create consistently-sized loaves without a scale. We’ll see…

As far as shaping is concerned, I will do my best to not use any bannetons. Everything will be hand-shaped. This means I will have to rely entirely on my dough development and shaping skills to produce loaves that will literally stand up. And as I write this, I’m actually pretty excited. In the back of my mind, I’m confident that I’ll be able to pull it off with good results. But as with anything, you never know until you see the finished product.

The Process

The first step in the process was to completely liquify the starter. This liquid would then be added directly to the flour as shown below.

Using a Danish dough whisk made quick work of bringing the liquid and flour together.

Once I had everything mixed, I dialed in the consistency of the dough by mixing by hand, adding a little extra flour and liquid as I didn’t feel I had enough dough. Mixing by hand at this point was important because it allowed me to really feel the dough.

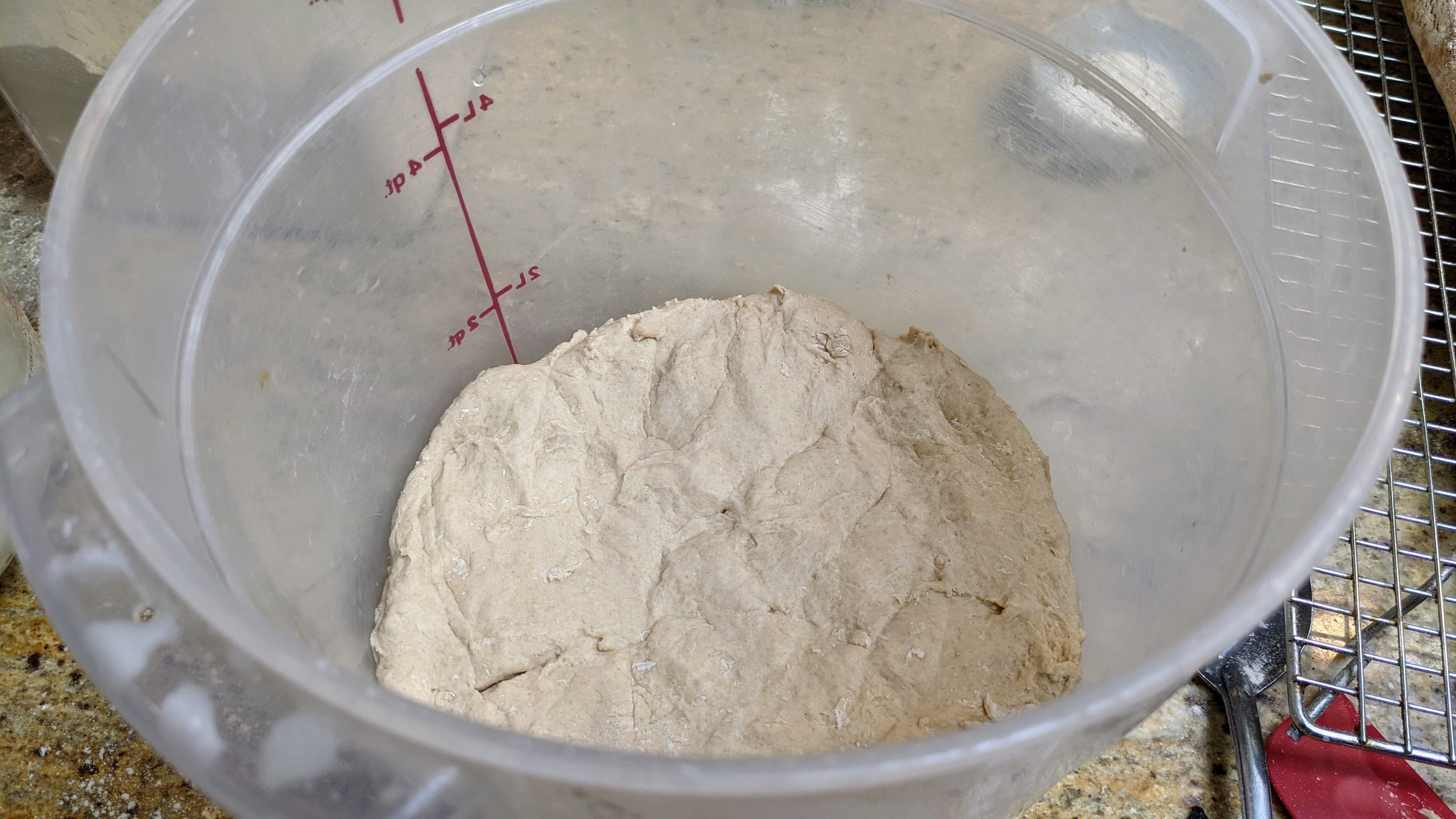

Once I dialied in the dough’s consistency, I transferred it to my bulking container to autolyse for 30-45 minutes. After that’s done, I’ll add the salt and a little more liquid to get to the approximate hydration (feel) that I want. There’s whole grain Kamut in this flour, so I’ll probably go a little wetter with the final dough.

I will admit that I’ll be leaning a lot on what I learned in Tartine N°3 in developing dough with whole grain flour. In that book, Chad Robertson employs his basic country loaf process, but has some valuable handling tips (read: being freakin’ gentle with the dough) accompanied by a fairly long final fermentation that has made a HUGE difference in how my whole-grain loaves come out.

After five sets of stretch and folds, the dough was super extensible, so I decided not to proceed with the sixth fold and let fermentation proceed untouched for another hour or so. Since I have a lot of high-extraction and whole grain flour in the dough, I need to be absolutely careful to not degas the dough and ruin all the work it has done the last two and a half hours.

I’ve mentioned in the past that I try not to be too parochial with recipes and techniques. That’s important because dough is affected by so many different factors. For instance with this particular batch of dough, about a third of the flour is really strong high-protein flour (17%+). I usually use it in conjunction with whole grain flour to help compensate for the bran that tends to cut the gluten.

But I have to say that at this point, the dough is feeling absolutely luxurious and is beginning to get nicely aerated. I should be shaping in the next couple of hours.

The Next Day…

Yeah… I was going to freestyle the loaves, but I ran out of time as I had plans for the evening. So I decided to shape up a couple of batards, put them in baskets and let them do their final ferment in my dough retarder. And yes, I did scale them out, though I got VERY close eyeballing them when I originally divided the dough and only fell about 20 grams short on one piece. Next time, I’ll probably just eyeball it…

But it’s probably best that I put the dough in baskets. When I was shaping the loaves, They felt like they were 90%+ hydration. Of course, I don’t know

The loaves are looking great in the oven right now! I was expecting the loaf on the left to be a little flatter than the one on the right as it came out of its banneton a little cockeyed. Oh well… But I’m loving the oven spring! With the predominance of whole-grain and high-extraction flour in my flour blend, I wasn’t too concerned about vertical lift. However, I was VERY concerned about overall spring and oven expansion. The wide fissure on each loaf indicates that the loaves expanded quite a bit and that pleases me to no end!

Notice how high up my baking stone is in my oven. I think I can go one more notch higher before my loaves touch the top. The reason I’ve got them up that high is that I used to have it down a few notches and I wasn’t getting enough steam on my loaves. With my stone higher up, all the steam created by my soaked towels and the water in the broiler pan at the bottom go right to the top of my oven. It’s kind of difficult to see in the picture, but the skin on each loaf at this point is quite damp. Since I’ve done that, my oven spring has been absolutely stellar!

I just pulled these out of the oven. I am VERY pleased with the results! Admittedly, it was a little nerveracking at first because I’ve been so used to being fairly exact with my measurements. But having gone through it and trusting in my dough development skills, I’m probably going to do this a bit more often.

That said, what I will definitely do is have predetermined flour blends that I normally use – I’ve been meaning to do this for a while anyway. This will make it easy to assemble my dough and take a little guesswork out of my different doughs’ performances so I should be able to achieve a fair amount of consistency.

Finally got a crumb shot of my loaves! Wow! I wasn’t expecting them to have such an open crumb because of all the bran in my dough. But hey! Who’s arguing? 🙂 I kind of felt as if I’d get a good crumb, because of the great oven spring, but did not expect it to be this good. In any case, the bread was a hit at the dinner party I attended this evening. It was a going-away-to-college party for one of my daughter’s friends so there were lots of teenagers there. They devoured the bread! I was quite pleased to see that!