One of the greatest compliments I ever received was from a friend’s mom who excitedly remarked when I brought her a few baguettes, “Wow! What bakery did you get these from?!” I told her they were from Dawg House Bakery. She replied, “Hmm… I’ve never heard of it,” to which I replied, “You’re looking at it and I’m the head baker.” She giggled then said, “They look SO professional!” She couldn’t have said anything nicer! But I did tell her that as with anything you build, if you have the right tools combined with good technique, it’s not hard to achieve a professional look.

Just to set things straight from the get-go, I’m not going to cover a recipe here or any dough development or shaping techniques. I’ve written lots of articles on making baguettes already. But what I am going to cover is what you do and what you need to have after you’ve done all the dough development and shaping; things that I’ve found tend to be glossed over in most articles – or even many books that I’ve read!

Tools

There are three critical items you’ll need: 1) A decent lame; 2) A baker’s couche; 3) A transfter/flip board. While I’ll discuss the importance of these items individually, you can purchase all of them at the San Francisco Baking Institute. The prices are fantastic – I wish I had known about their shop a lot earlier. I would’ve saved quite a bit of money.

Lame

I use a UFO lame from Wire Monkey (www.wiremonkey.com). But there are others out there that are far less expensive. A lame is essentially a mounted razor blade used to score loaves. More than any other bread, I’ve found this to be a critical tool for scoring baguettes.

Couche

You’ll read some articles that say you can use a large tea towel or a couche. I myself prefer a linen couche because I’ve found that it holds flour much better than a tea towel. It has become an invaluable tool for proofing long and free-form loaves.

Transfer Board

Out of all the three tools I’ve mentioned, a transfer board is the most important. With the lame and the couche, you can get away using alternatives, but having a tranfer board took my baguettes over the top. The reason is that I can flip the loaves onto the board at once, and not risk stretching or tearing my loaves.

Also, and perhaps even more importantly, I can use it to straighten my loaves once I’ve transferred them to my loading board. That’s a trick I learned from observing professional bakers. I was wondering how they straightened their loaves so nicely. I found that they do with a transfter board! For me, it was a total game-changer in the visual presentation quality of my baguettes.

If you don’t get the other two items, definitely get one of these. I made my own by cutting a sanded/finished quarter-inch birch plywood board to about 24″ X 5″. I used the remainder as my loading peel. With both, I regularly treat them with food-safe beeswax to keep them smooth and protected from moisture.

Properly Scoring Baguettes

I included this section in a previous article, but it deserved to be placed in this.

An earmark of a good-looking baguette is the scoring. It may or may not have ears, but it’s distinctive with what appear to be diagonal slashes across the top. When you’re new to making baguettes – this included me when I first started making them – there’s a mistaken belief with scoring that the loaves are scored in a diagonal fashion. Technically, they are, but not nearly at the extreme angles that many beginners score them. I’ve seen otherwise gorgeous, straight loaves online whose aesthetics were essentially ruined by improper scoring.

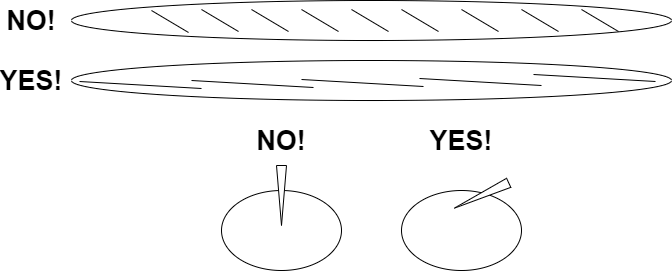

To be honest, there’s no big secret or special technique to score baguettes. Just remember this: Use shallow angles! The diagram below illustrates the angles you should be using:

In both the top and the cross-sectional views, the proper scoring and blade angles are much more shallow that what most might think. From the top, the lines are long, starting from the center of the loaf, and deflecting just a few degrees. The blade angle from the cross-section is absolutely critical as it creates a flap which will produce that distinctive ear that you see in the picture immediately above.

Especially with baguette scoring, you need to be assertive in your strokes. Avoid making choppy motions with your scoring and do your best to be as smooth as possible. Also, aesthetically – and according to Master Chef Jeffrey Hamelman – an odd number of scores is much more appealing to the eye than an even number.

As I mentioned above, with the right tools, getting that professional look is not at all that difficult to achieve!